I never intended to write this post. It feels like everything I have to say on the subject of Robin Williams’ suicide has already been said, and said better than I could say it. And there are lots of big and important subjects that I’m going to brush by glancingly, or dodge altogether.

But a post from a friend on Facebook today, and a conversation with my therapist changed my mind. Because I have a perspective that is uniquely my own, and I have a voice. And choosing to use that voice and share that perspective — choosing to be vulnerable — that to me is right at the heart of this whole issue.

I just gave away my thesis too soon. (Spoiler alert!) Let me back up and give some context. The things that have been the most upsetting to me in the debate following this tragedy (and every suicide is tragic) have been people saying that it was selfish to commit suicide. That Robin had to have known that people loved him.

Yes and no.

It’s been said many times before: depression lies.

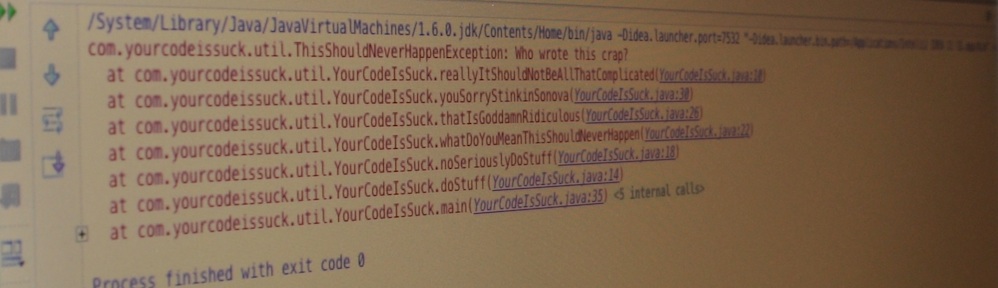

But the trick is it sounds like the truth. Not an objective truth, not necessarily even something that can stand up to the scrutiny of logic. Depression manifests in your own thoughts, your own feelings. Imagine your brain is a computer infected by a virus. Most of the time your thought processes are normal. But every so often the virus pops up a message on the screen: “You’re worthless”. Like a perverse memento mori, it reminds you of your own faults. It exaggerates and catastrophizes them. And when it’s really got hold of you, the virus consumes nearly all of your processing power. Normal thought can grind to a halt, starved for resources as malicious code rampages through your head.

At the deepest depths, you may know that you are loved, but the lie that says you aren’t feels more like the truth.

This can be helped; it can be fixed. But it is not easy. It usually takes professional help and a lot of effort. Very rarely can a depressed person “just snap out of it” or “just choose to be happy”. Trust me on this one: unless you have battled depression, you have no idea how hard it is.

Okay, so here’s something important. If any good can come out of Robin’s death and the media furor that’s followed it, it’s this: we, as a society, must stop stigmatizing mental illness in general and depression specifically. I’ve seen figures that say up to one quarter of Americans suffer from some sort of mental illness or addiction. (Citation needed.) Think about your family and your friends, your co-workers, anyone you feel you know well. Chances are at least one of them suffers from depression. I’m sure I know people who do, and don’t talk about it.

Which is exactly the problem.

I spent most of my adult life believing (in that depression-y “it feels true” kind of way) that being depressed was a character flaw. That it was not only my fault that I felt the way I did, but that I had to hide it. That I could be happy if only I would buck up. Or change my attitude. Or get more exercise. Or, or, or. The possible solutions are endless, and most of them are useless. What I didn’t do was talk to anyone about it. Because people didn’t want to hear it. Or so my depression told me. I know my family and friends are there for me, but I was ashamed.

Shame is worth talking about. Shame is the whip that depression uses to keep you down. Depression says “you’re worthless” and you believe it. Which creates a disincentive to open up to people, because (in the warped logic of depression) only scorn and rejection could possibly follow.

Imagine you’ve broken your leg. You can only move around on crutches and it hurts like hell all the time. Think about what the next few weeks would be like, how hard it would be to move around, to keep up with house-work. Think about getting to and from work, and sitting in uncomfortable conference room chairs. Without help from friends and family, (and painkillers, don’t forget the painkillers) you would be miserable and stressed and overwhelmed.

Now imagine that you’ve got a broken leg but you feel compelled to hide it. No crutches, no help from anyone, no acknowledgement at all of the constant pain and difficulty. You struggle through on your own because you couldn’t bear the shame if anyone found out that you had a broken leg, that you were injured.

That’s what it’s like to live with depression but try to hide it. It hurts all the time, but you feel like you can’t ask for help. We feel no shame for an injury. We shouldn’t feel any for an illness either, which is what depression is.

For those who aren’t afflicted with depression, the single most important piece of advice I have is to not minimize it. Don’t dismiss it, don’t trivialize it, don’t stigmatize it. Treat it like the illness it is. Give the afflicted love and support and understanding. Advice on how to get better, though well-meaning, is often not helpful, and may even be counter-productive. (For a much better explanation about this subject, read this. Especially the part about the fish.) I’m a fan of counseling, and I would advise anyone living with depression to get help. Beyond that, I think that empathy is your best bet.

For those of us with depression, the way we can meet our loved ones halfway is vulnerability. Vulnerability is like kryptonite to shame. (Don’t take my word for it. Watch this and this. (I know they’re long. They’re still worth watching.)) And depression without shame as a tool is largely defanged.

Which brings me (finally) back to why I decided to write this post. It’s kind of dual purpose. Choosing to share this, to be vulnerable in this way, can help me to combat my own depression. And if enough people do the same, and are met with compassion and acceptance, then maybe we can remove the stigma from depression. And then more people may feel comfortable getting help.

And maybe we’ll remember Robin Williams’ death as not just a tragedy, but as a turning point.

On Robin Williams and Depression

3

Follow

Follow